Kit Palmer | May 8, 2022

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

The First Family of U.S. Trials

There isn’t a family name more synonymous with U.S. trials than Belair: Fred and Martin Belair to be more specific. If it wasn’t for the Belairs, the sport of observed trials might not even exist in the U.S. and there certainly would be no El Trial de Espana, or Bernie Cup, for that matter—a pair of famous trials events you’ve probably heard of, even if you’re not a follower of trials.

You might associate the El Trial de Espana these days with Martin Belair, the former National and World trials competitor who is predominantly responsible for making sure the El Trial de Espana lives on, and you should. However, it was his father, Fred, who founded the event back in the early 1970s.

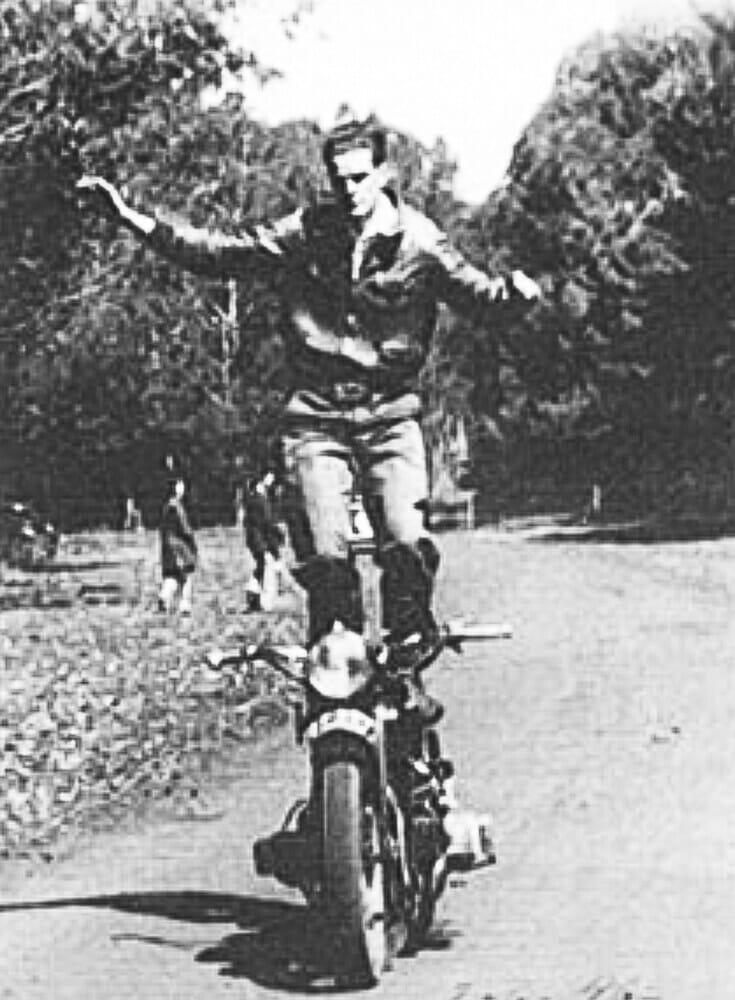

Fred was from Argentina and raced motorcycles as a kid, passing on his passion for motorcycles to his kids, including Martin, who was also born in Argentina. “His first two loves were my mom and motorcycles,” says Martin.

The family moved to Southern California in 1956 when Martin was a year old. “We started off on small bikes in the backyard and progressed up through Hodakas,” he says.

Martin’s first motorcycle was a Honda 90 that he shared with his brother, Fernando, but Martin says that technically his first motorcycle was built out of a Schwinn bicycle that Fred, his immigrant father who didn’t have a ton of money at the time, pieced together. “He made it himself! It had telescopic forks, a clutch, it had a McCulloch engine,” Belair says. “He made telescopes at the time [as a side job] and had a machine shop [to make the parts for the motorcycle].”

Eventually, Fred worked it out to where he could afford two Hodaka motorcycles, so Martin and Fernando wouldn’t have to share anymore. “Having to stop and share every 30 minutes really sucks as a kid. Your half hour is a lot shorter than his half hour,” says Belair. “I was about eight or nine when I finally had my own motorcycle.”

At that time, desert racing and motocross were the big things in Southern California. It’s what all the cool and famous motorcycle racers did, so Martin wanted to do the same thing as his heroes. But when Mom heard about the many injuries from racing a motorcycle 60 mph across the desert floor and on the MX tracks, well, she wasn’t exactly thrilled. “She was, ‘Hmm, no racing.’”

One day, someone (Cycle World magazine editor Ivan Wager, it turns out) suggested trials to Fred, and said there was a big trials event coming to Saddleback Park, so the Martins loaded up their Hodaka, which was still set up for desert racing, complete with an un-muffled expansion chamber and tall gearing, competed in his first trials competition, hosted by trials instructor Sammy Miller. It didn’t go well. “We had no idea what we were doing. We just tore the ribbons [which line the trials sections] up. I finished 17th out of 18 in the amateur class,” said Martin.

But he and his brother had fun. Afterward, they thought, “We can do better than this.”

The Belairs then read up on the sport of trials, watched some promotional films and modified their motorcycles for trials. Eight months later, Martin entered the Kid’s class and won. He got his first trophy and has been hooked on the sport of trials ever since. Martin eventually made Expert on the Hodaka.

“That’s how we got into trials, not because my dad was into trials—he had never even ridden trials. It turned into just a family thing, and it took off. There was the competitive aspect without any of the dangers. And that kept my mom happy.”

Martin continued to sharpen his skills at trials as did many other fledgling trials riders he rode with at that time. The southern California area became a hotbed of young and talented trialers, which included Marland Whaley, Bernie Schrieber, Bob Nichols, Bob Grove, Jack Ward (Jeff Ward’s father), Dave Evans (Debbie Evan’s father), and many others. The competition was stiff, to say the least.

“One point could mean the difference between first and eighth place,” Martin says. “It was so competitive.”

But these guys needed a place to hone and test their skills at the highest level, that place would be Europe.

“I found out later in life that my dad loved international competition. Being in Argentina, he always dreamed of going to Europe, but it was so hard for them to get there. So, when he saw all us kids here in California getting really good and progressing, he said, ‘These kids need to go to Europe.’ Then he organized the El Trial de Espana to raise money. The first year they sent Bob Nicholson and Kevin Walker, and by the third year, they sent seven of us. We went from local Southern Californian guys to riding a World Championship. I finished 140th, Marland was 139th, but in a few years, Marland was on the podium.”

Fred kept running the El Trial de Espana until it “got to be too much of a burden and turned it over to the [local trials] clubs,” says Martin.

Despite turning the El Trial de Espana to the clubs, Fred Belair remained heavily involved with trials and, more specifically, trials manufacturer Montesa, which was in Spain.

“My mom is from Barcelona, and my dad was at a trial at Saddleback Park one day, and the Montesa export manager was there, a very distinguished-looking man; you know, goatee, turtleneck, sport coat. At Saddleback, he really stuck out. My Dad is going, ‘Who is this guy?’ Here we are riding Hodakas and my dad, who speaks Spanish, went up to talk to him, and that was the beginning of a relationship with Montesa that has lasted still to this day.

“The executives from Spain would come over to our house and my mom would cook them Cantalan food, it became a family thing. Montesa has always been family with me. People assume that Fred was an importer, or partner, but he’d always say, ‘I don’t want to ruin our friendship [with Montesa],’ because getting into business together might spoil their friendship. They offered him the importership several times, but he always turned it down.”

My dad was at a trial at Saddleback Park one day, and the Montesa export manager was there, a very distinguished-looking man; you know, goatee, turtleneck, sport coat.”

Over time, Fred made a lot of connections in the motorcycle industry despite not working in the motorcycle industry. “He was very open and would talk to anybody,” says Martin. “We’d go to Inter-Am races, and he’d go right up to Joel Robert and start talking to him, and [Roger] DeCoster. He was a charming guy.”

Martin connected with Montesa, as well. He first rode for Montesa then moved to Spain and worked at the factory. “That was almost the training ground for the rest of my life,” he says. “They moved me all around the factory, into just about every position. It was like they were grooming me [for something].”

Martin eventually returned to the States and Costa Mesa, California, and worked for the Montesa importer. He did, in his words, “take the 1980s off.”

“I didn’t ride motorcycles or anything. I had three brand-new daughters. When they got older, we moved to Minnesota—decided to make a change. We were there for about 12 years. Great place to raise a family.”

In the 1990s, Martin got back into the motorcycle business again as Montesa’s U.S. importer —on the side. He already had a “real” job working in the painting business, helping design painting equipment. “It was a good job, it had benefits, my kids could get braces,” he says.

Martin ran his importing business out of his home, in the garage to be exact, in between his regular 40-hour-a-week job. “I never had commercial space, always did it out of my home. It all worked out and I’m really grateful for it.”

When the economy went off the cliff around 2010, Montesa came out with its fuel-injected four-stroke which brought with it a larger price tag, which came at a bad time when the exchange rate went through the roof. As a result, there was a gap when Montesa, as well as other manufactures that sold trials bikes, such as Honda, stopped importing trials bikes. “We were priced out of the market,” says Martin.

However, both Montesa and Honda felt there was a market for trials bikes in the U.S. and the two manufactures worked out a deal to get Montesa, and Honda, back in the U.S. market in 2014. “Montesa is Honda,” says Martin. “People find it hard to separate what is what, but I tell people, ‘Acura is a Honda.’ It’s just a different market segment. Montesa is Honda’s trials division. Honda saw that Montesa had all this knowledge about trials, and trials is important to Honda. It’s a great R&D platform for them. There’s a Honda factory in Barcelona where Montesa’s are made. It’s the same facility where Honda runs its MotoGP team, Dakar, it’s like 12 different companies—Honda entities—at this one facility. The bike is a Honda.”

Martin is still heavily involved with Montesa/Honda. “I’m contracted with American Honda in Spain, and I run the U.S. trials team. I travel to all the U.S. trials events, major events like the UTE Cup, and represent Honda/Montesa and take care of our riders. That’s Honda’s main concern—to take care of the guys that bought the bike. In the past we’ve had pro riders, we’ve won championships, but we now only take care of the amateurs, everybody on a Honda. Honda wants to focus on the customer, not the pro guy. People say, ‘You don’t have a team,’ but there are 18 guys [amateurs] I support, and anybody else on a Montesa. I can help 20 guys for the cost to support one pro rider. These are the guys that bought the bikes, the customers. It’s been a real eye-opener.”

So, as you can tell, Martin is keeping his father’s legacy alive while also still doing his best to grow the sport of trials in the U.S. So, the next time trials comes to your town, do yourself a favor and look for the Montesa and Honda logos in the pits and strike up a conversation with Martin Belair and talk trials. He’ll love it. CN

Click here to read the Archives Column in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Subscribe to nearly 50 years of Cycle News Archive issues

Click here for all the latest Off-Road Racing news.