“What are eight million dollars compared to the love of eight million Cubans?”

That was the response of Cuba’s late, great, Olympic champion Teofilo Stevenson each time he was asked why a fight with Muhammad Ali never materialised in the 1970s.

In 1962, Cuban boxers were banned from cashing in on prize fights.

Not long after taking power, Fidel Castro banished professional sports, focusing the nation’s athletes on Olympic and amateur contests.

Pugilists were left with an impossible choice – stay home and box for a humble communist wage or leave their beloved homeland and families in pursuit of mainstream glory.

But on 20 May, in the city of Aguascalientes in Mexico, Golden Ring Promotions hosted a show in conjunction with the Cuban Boxing Federation (CFB) allowing its boxers to compete professionally for the first time in six decades.

“For many years we have studied the possibility of entering the professional rankings,” Golden Ring president Gerry Saldivar told the BBC.

“There must be an organic, progressive and smooth transition. It’s an exciting moment for Cuban boxing and world boxing in general.”

‘My greatest fear was being forgotten’

Six elite Cuban boxers impressed at the inaugural event, five with stoppage wins. Among them were Olympic champions Julio Cesar la Cruz, Roniel Iglesias and Arlen Lopez, who beat Ben Whittaker at the Tokyo Olympics.

Yet pockets of scepticism still surround the deal.

Why has the CFB now changed its stance – and why is a relatively unknown Mexican organisation involved with the deal?

Having served as a consultant to Cuban Boxing since 2013, Saldivar feels his company is the perfect partner to revolutionise the sport.

Purse percentages were split 80/15/5 between fighter, trainer and medical staff – a wage share agreed for all the shows. While Saldivar’s vision sounds promising, it’s hard to predict if the deal will spawn more champions.

One fighter unwilling to wait to find out is Kevin Hayler Brown. One of Cuba’s top-rated amateur welterweights, he left the island in March, convinced the traditional voyage is the most likely route to professional success.

“I did not sign that agreement with Golden Ring Promotions. Now I am out of Cuba with dreams of fighting in the United States for a title,” Brown said through Instagram.

The move could be interpreted as a vote of no-confidence in Golden Ring’s plans, however the 28-year-old’s frustrations seem steeped in having been let down in the past.

“My greatest fear was staying there and being forgotten, like so many champions of the past,” added Brown.

“If you seek happiness and a greater purpose that you do not find in your country, a decision must be made for the improvement of yourself and family.

“If I’d stayed, I’d have to continue putting up with lies and deceit. I wasn’t going to waste my time on something uncertain.”

Will international recognition follow for pro boxers?

Another voice hesitant to heap praise on the arrangement is that of Irish promoter and manager Gary Hyde.

“I love the Cubans, but I’m not sure they’ve got the right people to guide them,” he said. “They should be bringing young 18 and 19-year olds through, not concentrating on older Olympians.”

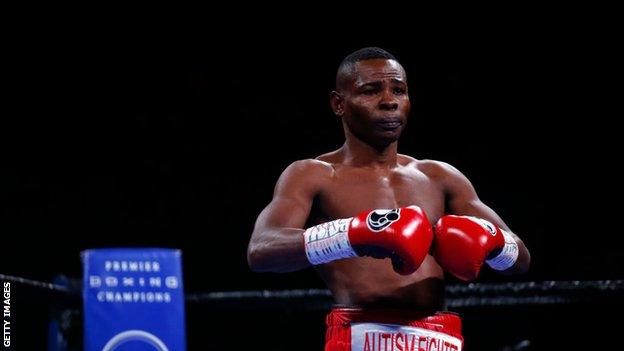

Having signed a number of exiled Cuban fighters in the mid-2000s – including possibly the country’s greatest talent, Guillermo Rigondeaux, Hyde has lived the difficulties of professional boxing.

“There’s just so many tricks to learn,” he added. “The governing bodies are not just going to start ranking these Cubans, that’s dreamy stuff.”

It’s not an issue lost on Saldivar, who is open to work with other promotional companies, confident his signings will eventually “have the quality to fight the best”.

Yet Hyde’s worries don’t end at the organisational aspect of the deal. He believes the temperament and style of the island’s fighters could be problematic, especially for those turning pro at an advanced age.

Rigondeaux was 29 when he did back in 2009 – and was undefeated for eight years until beaten by Vasiliy Lomachenko for the WBO junior lightweight title.

“There’s no distractions back home [in Cuba], everything’s catered for and they’re totally in the flow of life. The punches just come off over those three-round amateur bouts,” recalled Hyde.

“When you bring them to the pros and it’s six rounds, eight rounds, they lose their concentration.

“Rigondeaux would get to about the seventh and he’d switch off, looking into the crowd. We’d literally have to shake him to wake him up halfway through the fight.”

‘Almost all Cubans suffer from PTSD’

Few would argue most fighters who leave Cuba fail to achieve what their amateur pedigree promised.

But when comparing records to professionals from other nations, film-maker and author of The Domino Diaries Brin-Jonathan Butler feels a unique context needs to be applied.

“Almost all Cubans arriving in the United States, before they even step into a ring, are suffering from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder),” Butler explained.

“It’s Cuba’s answer to Sophie’s Choice. This could be the last time they see anybody or anything they love from their homeland. To understand their psychology, you have to understand that trauma.”

Having directed Split Decision: The Guillermo Rigondeaux Story, Butler says if an agreement like the one with Golden Ring had previously been in place, Cubans might have made more of an impact on the pro ranks.

“There’s a tremendous amount of prejudice towards Cuban boxers,” he added. “So many American writers look at Floyd Mayweather as a great genius and treat Rigondeaux as the most boring fighter we’ve ever seen. Aesthetically, there’s no consistency in that appraisal.

“Say Rigondeaux turns professional at 18, you might have had 13 years of him being undefeated. The young Yuriorkis Gamboa was Mike Tyson – so vicious and ferocious, so athletically gifted. You just need someone like that as a gateway for the world into Cuban fighters.”

Only time will tell if Brown has made the right decision to leave Cuba – or if Golden Ring Promotions can solve a complicated boxing dilemma.

One thing is for certain, though. At a time when Cuba is paralysed by post-pandemic struggles, the nation’s boxers finally have options and greater hope.